Bravery and the Blitz - nursing staff adapt to wartime

The Covid-19 pandemic isn’t the first crisis the nursing staff at the Royal Hospital has had to cope with. During the Blitz, the Royal Hospital was under constant threat and 13 lives were lost when the Infirmary was bombed during the Blitz. Then, as now, the tireless Royal Hospital nurses showed their courage and commitment to their Pensioner patients.

Changing times

Throughout World War II the nursing staff – generally a matron, four nursing sisters and 20 nurses – had to adapt to constantly changing circumstances. On the eve before war broke out, 50 Pensioners were evacuated to Rudhall Manor, together with nursing sister and five nurses. The remaining Pensioners and staff stayed at the Royal Hospital – perhaps partly due the risk of the building being taken over by the government if it was vacated.

A nursing sister and five nurses watch the Founder’s Day parade at Rudhall Manor in 1940

Tragedy at the Infirmary

The Royal Hospital’s War Diary records the events of 16 April 1941 in vivid detail:

“The alarm sounded at half an hour after black-out and soon afterwards about 9 or 10 enemy aircraft began passing overhead. From this time until 4am the air was full. Several machines being within earshot. Two during the night appeared to be diving bombing and it is thought they may have been out of control and were about to crash (one did so in Kensington).

About 11.18 there was an extremely heavy explosion without previous warning, evidently from a landmine. Clouds of dust filled the air, debris fell within a 300-yard radius of the Infirmary. The east wing was completely destroyed, a large crater occupying the site. The remainder of the Infirmary was badly damaged, the roof being removed. Though luckily an air raid shelter remained intact. Windows were broken all over the Royal Hospital.”

The site of the Infirmary’s east wing after the bombing

Nurses in danger

In his memoir, Captain Townsend records a poignant encounter with Sister Nicholson before she lost her life in the tragedy:

“As I knew the Infirmary was not a very safe place, I used to beg them to come over to their First Aid posts at half past five, when the In-Pensioners went there. However, they would insist on staying in the Infirmary for their evening meal, and then come over to their First Aid post. One of them [Elizabeth Nicholson] said to me: ‘We’re all right in the Infirmary, and if there’s a bad raid, I’ve got a very safe place to go to.’ I asked her where that was, and she said: ‘Underneath the stairs’. Well, the morning after the Infirmary was destroyed on the 16thApril 1941, we found her. She was in what she thought was a safe place, under the stairs, but she’d been killed”.

The War Diary records how another nurse had a narrow escape – and demonstrated the dauntless spirit of the Royal Hospital’s nursing team:

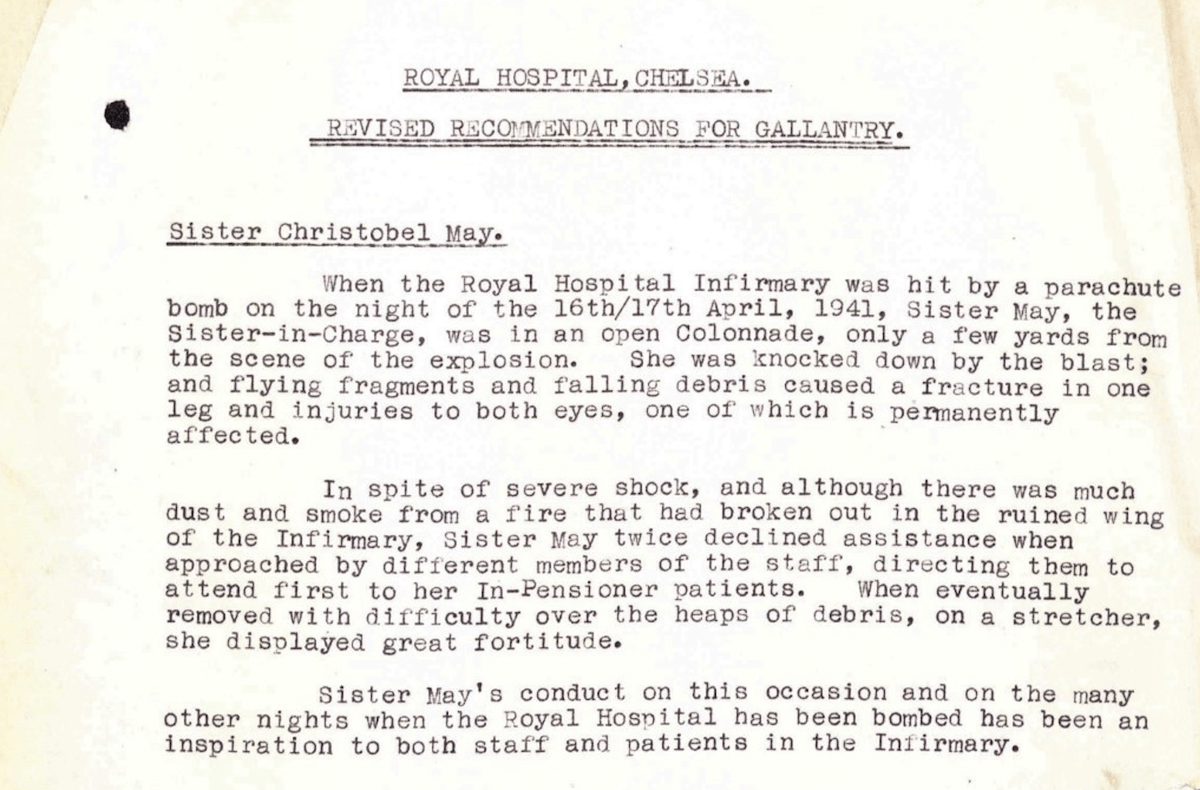

Sister May’s recommendation for gallantry

Subsequently, Sister May was among the nurses recommended for gallantry by the Royal Hospital’s Commissioners in recognition of their bravery during the bombing.

The aftermath of the attack

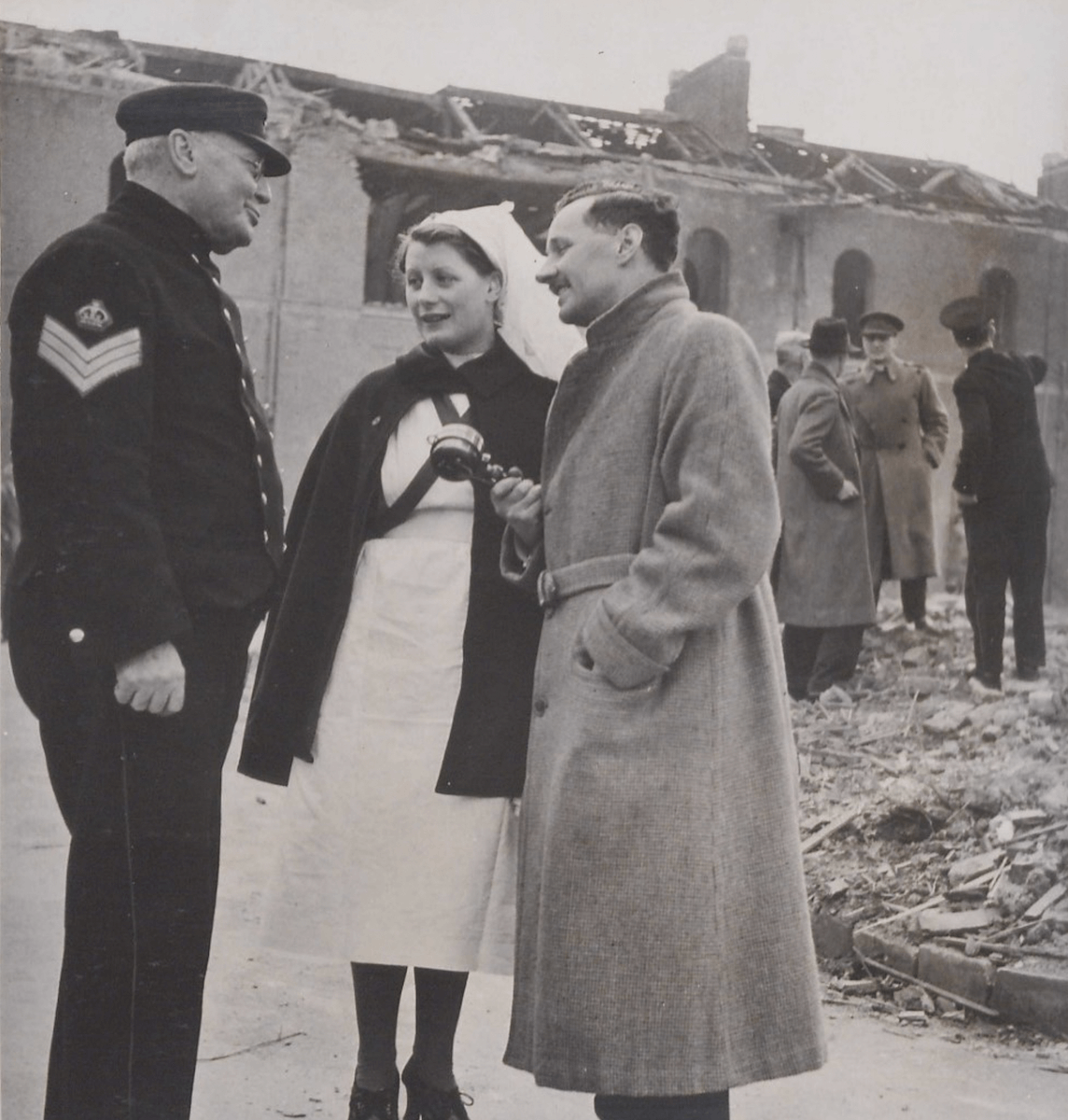

The journalist Lewis John Wynford Vaughan-Thomas visited the site of the bombed Infirmary to interview survivors. Although the Pensioner is named as J.J. Jones, the name of the brave and cheerful nurse alongside him has been lost.

Journalist Vaughan-Thomas, Pensioner J. J. Jones and a nurse in the aftermath of the bombing

In the aftermath of the attack, a replacement Infirmary was established at Ascott House in Leighton Buzzard, staffed by the matron and nurses from the bombed building. Another nurse, Sister Leadbetter, was sent to care for Pensioners billeted at Moraston House in Ross on Wye. Meanwhile, a physician and surgeon, dispenser, orderly and a sister and a nurse were stationed at Rudhall Manor to look after the Pensioners there. By mid May 1941, only one orderly sister and one nurse remained at the Royal Hospital – the risk to their lives was felt to be too great.