From its extravagant beginnings as part of the estate of the 1st Earl of Ranelagh, Richard Jones (1641-1712), to its fashionable pleasure gardens and impressive rotunda, Ranelagh Gardens at the Royal Hospital Chelsea have boasted a long and fascinating history.

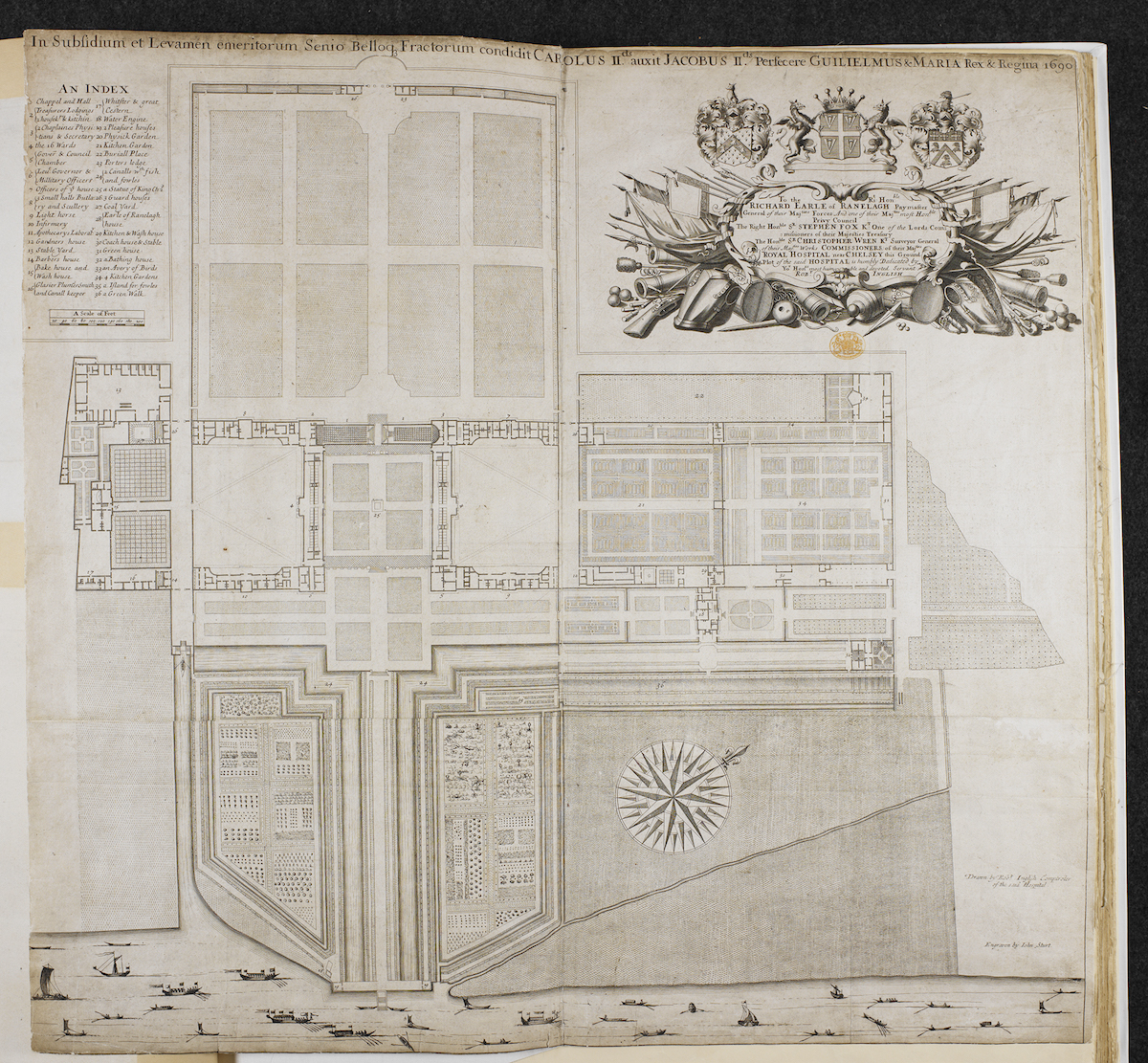

The earliest plan of the Royal Hospital’s grounds, drawn by its first Comptroller Captain Robert Inglish (d. 1715), reveals several interesting features. Dated 1690, the plan shows ‘Cannalls with Fish and Fowl’, a ‘Bakehouse and Wash House’, and ‘An Aviary of Birds’. Of particular note are the ‘Physick Garden’ and ‘Apothecary’s Laboratory’, which allude to the Royal Hospital’s early history of producing and distributing its own medicines to the Chelsea Pensioners and its staff.

The Ground Plot. Drawing by Robert Inglish. Engraving by John Sturt (1658-1730) © British Library Board. Cartographic Items Maps K.Top.28.4.c.

‘Physick Garden’

First established at monastic institutions during the reign of the Emperor Charlemagne (800-814), physic gardens are herb gardens where medicinal plants are grown. The ‘hortus', or garden, at the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland included a 'herbularis’, or Physic Garden, near the doctor’s house, the sole purpose of which was to grow medicinal plants (Hill, 1915).

Inglish’s plan is evidence that, towards the end of the 17th century, Chelsea was home to not one, but two, physic gardens. Unlike the neighbouring Chelsea Physic Garden, founded in 1673, the Royal Hospital’s physic garden no longer exists. Historic accounts and plans show that it was located next to our historic burial ground, which survives today. At over 50 feet wide, the garden boasted fruit trees, borders planted with herbs and a small two-storeyed building which housed the Apothecary’s laboratory.

Scales, Royal Hospital Chelsea

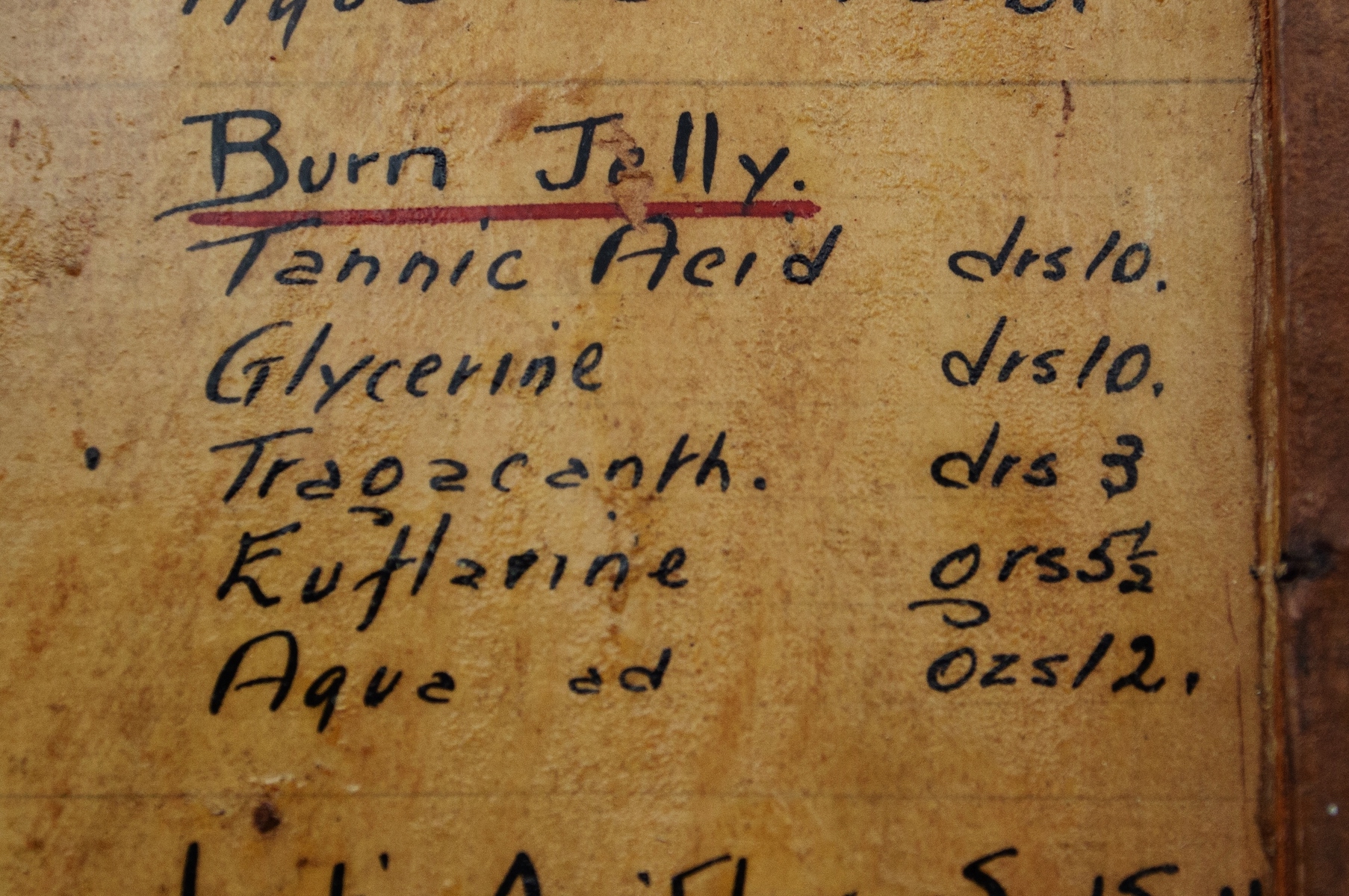

Apothecaries were responsible for producing and prescribing medicines for the Royal Hospital’s staff and resident veteran population. Their laboratory was equipped with a furnace, mortars, earthen bottles, pots, glasses and scales for measuring ingredients and preparing medicines. In his account of the history of the Royal Hospital Chelsea, Adjutant and Captain of Invalids C.G.T. Dean suggested that the isolated location of the laboratory was chosen to ‘avoid annoyance from the noxious fumes caused through concocting drugs’.

Following Apothecary William North’s decision in 1820 to purchase medicines from Apothecaries’ Hall on Black Friars Lane, the laboratory was converted into accommodation for the Governor’s gardener. Around 1850, it was demolished after being described as “a great Eyesore to the Establishment” by the Royal Hospital’s resident Physician.

‘The charitable apothecary’

Queen Mary II (1662 – 1694) by Godfrey Kneller (1646 – 1723), Royal Hospital Chelsea.

Garnier was one of the many Huguenot refugees who came to England from France towards the end of the 17thcentury following the revocation of The Edict of Nantes (1598), which had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without persecution. Garnier’s appointment is attributed to Queen Mary II who reputedly ‘retrenched in order to relieve the Huguenot refugees, who were starving in the garrets of London’ (T.B. Macaulay).

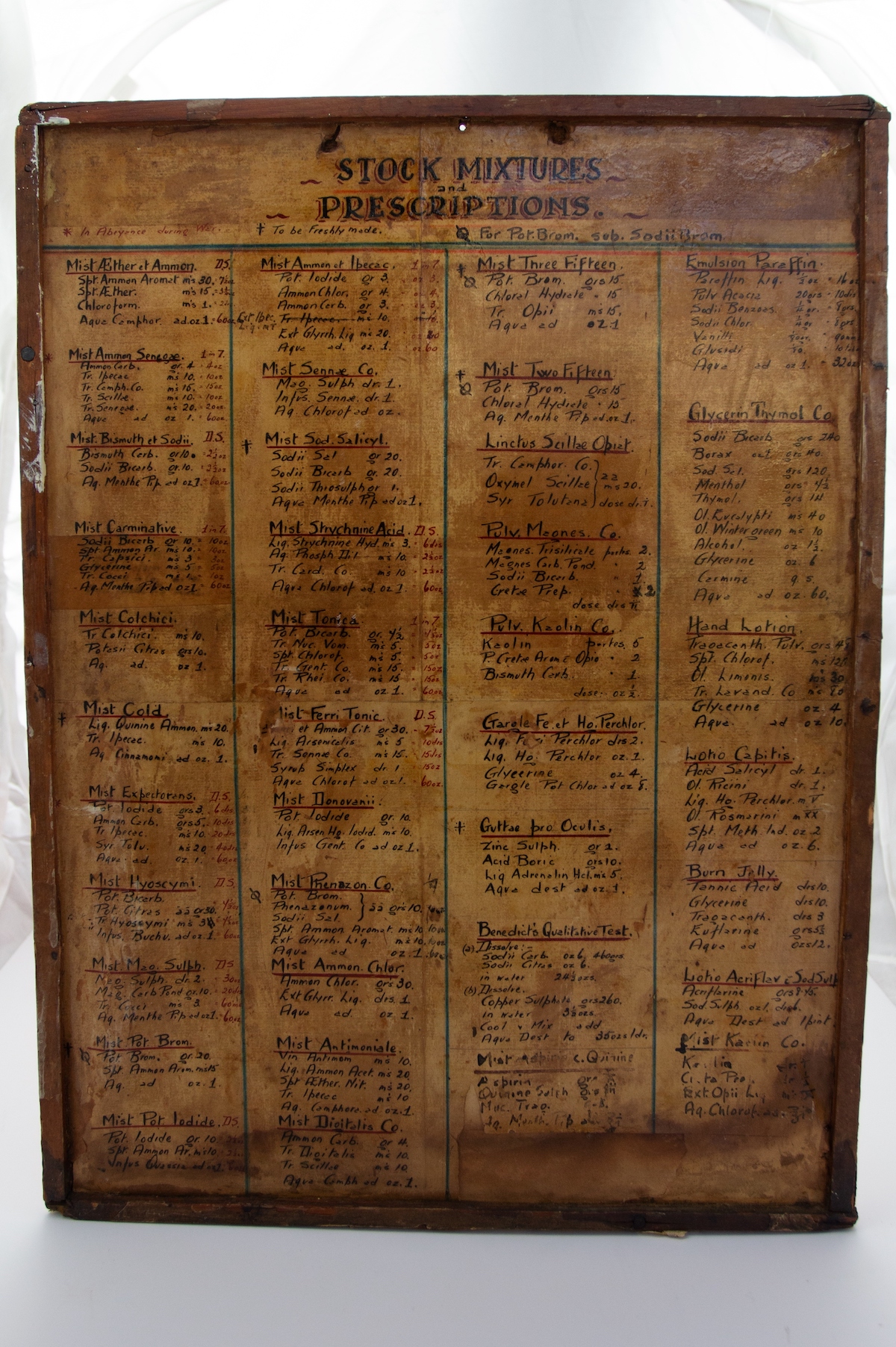

Prescription board, Royal Hospital Chelsea.

The family business

Following the tenure of three different members of the Garnier family, Daniel Graham held the position of Apothecary at the Royal Hospital between 1739 and 1747. Described by the eminent writer and politician Horace Walpole as one of ‘the most eminent apothecaries of the day’, Graham prospered from the sale of medicines and used his own money to build a small shop in the physic garden. In addition to his appointment at the Royal Hospital Chelsea, Graham served as Royal Apothecary to King George I and King George II. The family’s affluence is evident in this portrait, painted by William Hogarth in 1742, now in the National Gallery collection.

Graham was succeeded by his son Richard Robert Graham, pictured seated below the gilded bird cage, who ‘never troubled to acquire any professional training’ (Dean, 1950). Richard’s unsuitability to the post was subsequently recognised in the XIXth Report of the Commissioners of the Royal Hospital Chelsea, which noted that ‘the present holder of the Office is not an Apothecary by profession’. The Report recommended that ‘a competent Medical Person, who has served in the Army in the capacity of a Surgeon or of Apothecary to the Forces, be appointed to the situation by a Commission’.

"He may be said to have been maintained by the Royal Hospital, from his cradle to his death-bed in 1816, in comparative affluence and complete idleness"

C.G.T. Dean (1950) on Richard Robert Graham

End of an era

As the consumption of medicines by staff and the Chelsea Pensioners surged, ‘eventually attaining astronomical proportions’, the Apothecary benefited from increased profits which they received in addition to their annual salary (Dean, 1950).

Responding to the exorbitant prices charged to purchase medicines, Lord John Russell (1792-1878), a prominent politician and later Prime Minister, became interested in the Royal Hospital’s approach to staffing and determined that a radical revision was needed. Having obtained the agreement of the Prime Minister, 2nd Earl Grey, a Royal Warrant was issued on the 3rd August 1833 which called for all unnecessary offices to be abolished. As a result, the position of Apothecary to the Royal Hospital had ceased to exist by 1846.

Though we no longer produce our own medicines, the Royal Hospital Chelsea continues to provide healthcare to our resident veteran community in the latest chapter of a distinguished and unbroken history of medical care since 1692.