From delivering post, to guiding visitors around our historic site, the Chelsea Pensioners can choose to take on a number of different jobs while living at the Royal Hospital. One of the more unusual roles previously adopted by Pensioners was as a member of the Chelsea Patrol; a London garrison stationed between the Royal Hospital and St James’ Palace to deter against criminal activity and protect the city against the growing threat posed by the Jacobite movement.

The Jacobites

‘Jacobite’ was the name given to supporters of the Catholic King James II (1633-1701) and his descendants, who were exiled during the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The Jacobite movement supported the restoration of the House of Stuart to the British throne and posed a significant political threat in the late 17th and 18th centuries.

James II had ascended to the English throne in 1685, a time of tense relations between Catholics and Protestants. Relations were strained further when, in 1687, James issued the Declaration of Indulgence which granted broad religious freedom by suspending penal laws against Catholics. Intended to promote Catholicism, the Declaration was condemned by Anglicans who argued that it permitted the practice of any religion, including paganism. The King’s decision to formally dissolve Parliament in favour of one that would support him unconditionally and the birth of his Catholic son left many fearful that a Catholic dynasty was imminent. In the Glorious Revolution of 1688, with the support of many of King James’s peers, James’s Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William of Orange, deposed the King and succeeded to the throne.

The Jacobite Rising of 1715

In 1714, the British throne passed to King George I and the house of Hanover after Queen Anne, Mary’s sister, died without an heir. In August of the same year James Francis Edward Stuart, son of the exiled King James II, issued a handbill calling on the Jacobites to restore the House of Stuart to the British throne:

‘It is plain our People can never enjoy any lasting peace or happiness’ till they settle the succession again in the right Line, & recall us the immediate Lawfull Heir, & the onely born English-man now left of the Royall family.’

A handbill from James III, James Francis Edward, ‘The Old Pretender’ son of James II of England, August 1714 (SP 35/1/f30). The National Archives.

The Act of Union in 1707 had prompted the union of England and Scotland under the name of Great Britain. This was unpopular in Scotland, where the Jacobites seized the opportunity to assert themselves as defenders of Scottish liberties by pledging their intent to repeal the Union and restore Scotland’s parliament. While the rebellion was primarily concentrated in Scotland, following the mobilisation of Highland clans and a military force numbering 16,000 men, the Jacobite threat was felt as far away as London. A contemporary report from John Blackwell, a Constable of the Ward of Cheapside in London, to the authorities describes the nature of threats to King George I ‘s rule in the capital:

‘This Informant had certain Inteligence on the 29th May 1715, that there was a design laid to raise three Mobbs in the City of London that Night... to secure, or sieze on the Bank of England or set it on Fire: Also to Assassinate & Murder such Magistrates of this City as had appeared Zealous for his Majesty King George, or to set their Houses and Habitations on Fire... and to raise Mobbs in all places in the Country...to pave the way for an open Rebellion, and to give an opportunity and Encouragement to the Pretender and his Adherents, [to] land with a Foreigne Force who was said Lay ready, for that Purpose.’

Report from John Blackwell, Constable of the Ward of Cheapside in London, to the authorities, 20 June 1715 (SP 41/5 f24). The National Archives.

In September 1715, in response to this growing unrest, King George I issued a Royal Warrant that established the Chelsea Patrol. It has also been suggested that the Patrol was formed at the request of Sir Robert Walpole (1676-1745), Britain’s first Prime Minister, out of concern for his personal safety (Dean, 1950).

Highwaymen and Footpads

In addition to supressing Jacobite violence, it was hoped that the Chelsea Patrol would deter against crime on the remote roads around Chelsea which, towards the end of the 17th century, had developed a reputation for highway robbery and violent crime.

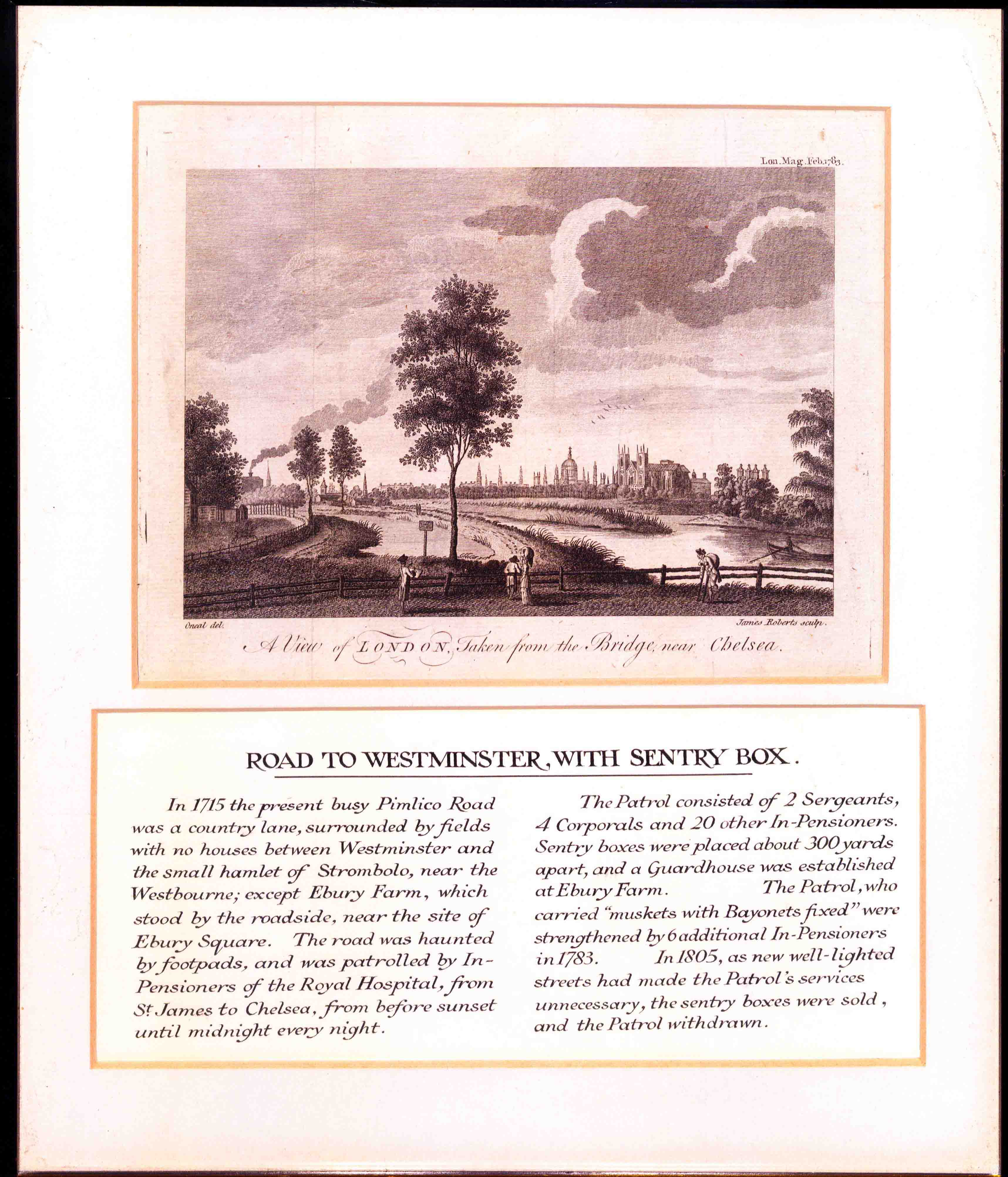

This print from the Royal Hospital Chelsea’s collection shows a view of London from Chelsea that appeared in The London Magazine in 1783. While Westminster Abbey and the iconic dome of St Paul’s Cathedral can be seen in the distance, the print illustrates the seclusion of the roads around Chelsea. Roads that are now busy with people and traffic were country lanes, surrounded by fields and populated with few houses.

It was common for highwaymen to target woodland and remote, unlit roads leading into London with the intention of stealing from passing travellers and committing acts of violence. The text accompanying the print tells of roads ‘haunted by footpads’, the term for thieves who targeted pedestrian victims in contrast to highwaymen who rode on horseback and stole from people travelling in carriages.

The Chelsea Patrol

The Chelsea Patrol was made up of 20 In-Pensioners, 4 Corporals and 2 Sergeants. Pensioners were specially selected and were stationed between a Guardhouse and several sentry boxes situated along the dark roads between St James’ Palace, Buckingham Gate, and Chelsea. They patrolled from sunset until midnight, carrying lanterns on long poles and muskets with fixed bayonets, and received financial compensation in recognition of their service.

The work could be extremely dangerous. In 1716, an attack on the Patrol resulted in the death of one Pensioner and another was severely wounded. The Patrol’s number increased in 1783 in response to an alarming increase in robberies in the area. However, by 1805 improved street lighting on the highways meant that their work was no longer deemed necessary. The Royal Hospital’s Governor, General Sir David Dundas, made the decision to disband the Patrol in order to support the Hospital’s duty of care to its Pensioners.

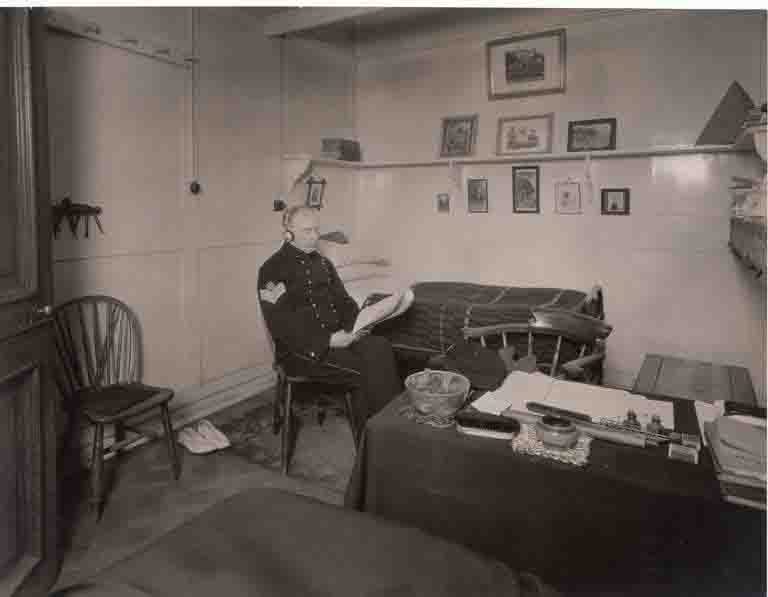

Though the Chelsea Patrol has not been operational for over 200 years, its work is still remembered at the Royal Hospital. While taking a tour of The Royal Hospital you will visit our Heritage Berth, where you can see an example of a Sergeant’s room where the Patrol’s muskets would have been stored.