Today marks 80 years following the bombing of the Royal Hospital’s Infirmary during the Second World War. The magnificent Infirmary, which once stood on the current site of the National Army Museum, was hit by a parachute bomb on 16 April 1941 – destroying most of the building and tragically ending the lives of 13 people. Although nothing remains of the original building designed by celebrated architect Sir John Soane, the extraordinary acts of bravery exhibited that night and the memory of those who lost their lives were honoured in small wreath-laying ceremonies across the Royal Hospital Chelsea and National Army Museum sites today.

An imposing building

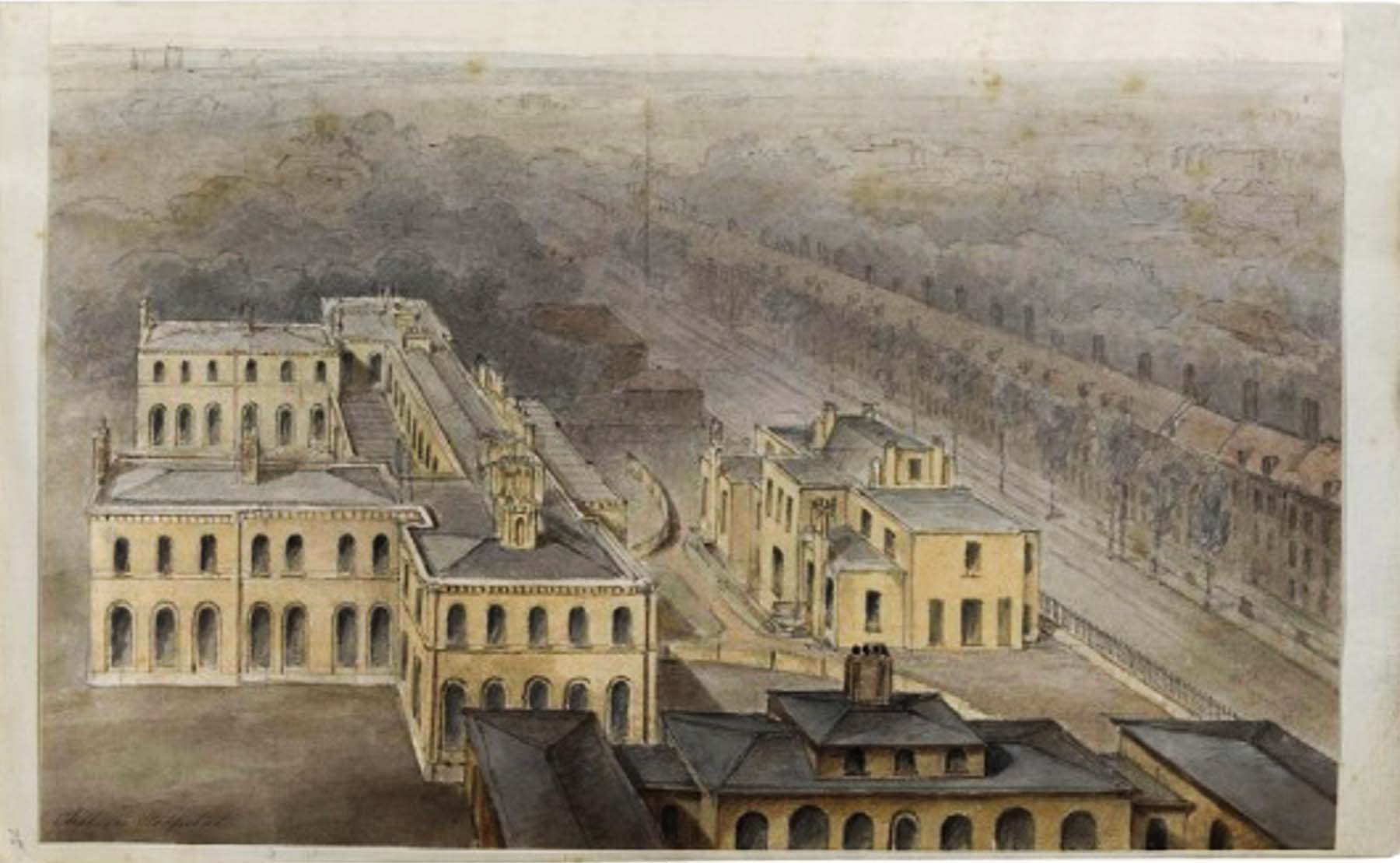

Sir John Soane –who designed the Bank of England – left his mark on our site during the 19th century. His impressive Infirmary was built between 1818 and 1833 on the north-west side of the Hospital, set back off of Royal Hospital Road.

The Infirmary dominated the Royal Hospital Road

The Infirmary seen looking North from where the car park is today.

This photograph of the Infirmary shows the ivy-covered West Wing extension. The nurses used to reach their accommodation in Gordon via the covered walkway on the right.

This view of the Infirmary’s interior was taken in the early 20th century.

A war-time tragedy at the Royal Hospital

When World War II broke out, 52 Chelsea Pensioners and seven members of staff were evacuated to Rudhall Manor near Ross-on-Wye. However, around 600 staff and residents remained on site, including the Governor General Sir Harry Knox and bed-bound Pensioners whose needs would not have been catered for at Rudhall.

During air raids, nursing staff took turns to watch over them in the Infirmary as it wasn’t practical to move them to air raid shelters.

Disaster strikes

On 16 April 1941 an aerial mine hit Sir John Soane’s Infirmary damaging the building so extensively that it was eventually demolished.

The Royal Hospital’s War Diary records the incident in vivid detail:

“About 11.18pm there was an extremely heavy explosion, without previous warning… Clouds of dust filled the air, debris fell within a 300-foot radius of the Infirmary. The East Wing was completely demolished, a large crater occupying the site. The remainder of the Infirmary was

badly damaged, the roof being removed… Windows were broken all over the Royal Hospital. Those in the bombed wing were killed outright.”

On duty were the Sister in Charge, Christobel May, and nurses Adela Howard, known as Florence, and Hannah Deasy. Ward 7 was destroyed and everyone inside was killed instantly. Forty Pensioners and staff were trapped in the rubble.

Nurses Howard and Deasy were among those who climbed through the ruins to rescue trapped and bed-bound Chelsea Pensioners.

An eye-witness account of the bombing

Sir John Soane’s beautiful building is reduced to rubble.

“We were just turning down Tite Street when we saw two parachutes floating down… After what seemed a lifetime there followed two long, dull roars and then an appalling explosion.”

While they were being treated for their injuries they discovered the significance of the parachutes: “…we knew from a warden who came in that one of the parachutes we had seen had landed on the Infirmary of the Royal Hospital and that there were over forty old Pensioners and nurses trapped there.”

The building blazed as the emergency services struggled to get through to the Infirmary. Meanwhile brave men and women put aside their own safety in their attempts to rescue those in danger at the Royal Hospital.

Remembering the victims

Five staff and eight Chelsea Pensioner patients were killed in the Infirmary bombing, including nursing sister who Edith Taylor had settled the evacuated Pensioners into Rudhall Manor before returning to the Royal Hospital in January 1940. She was on duty in Ward 7, at the top of the Infirmary, on the night of the bombing. The Pensioners in the ward included 100-year-old Pensioner Rattrey. Both were killed when the blast hit.

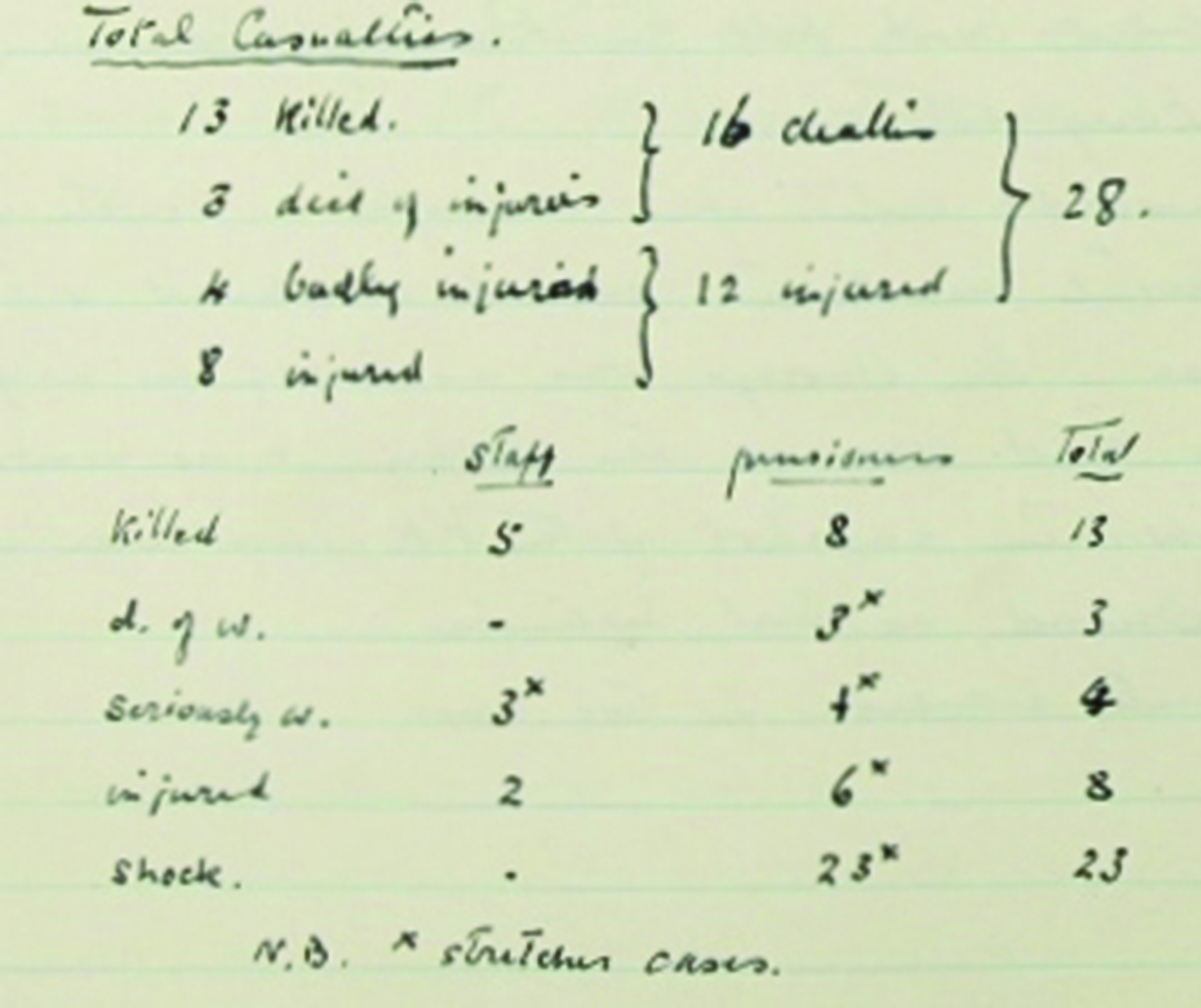

The casualties from the Infirmary bombing are recorded in the Royal Hospital’s War Diary.

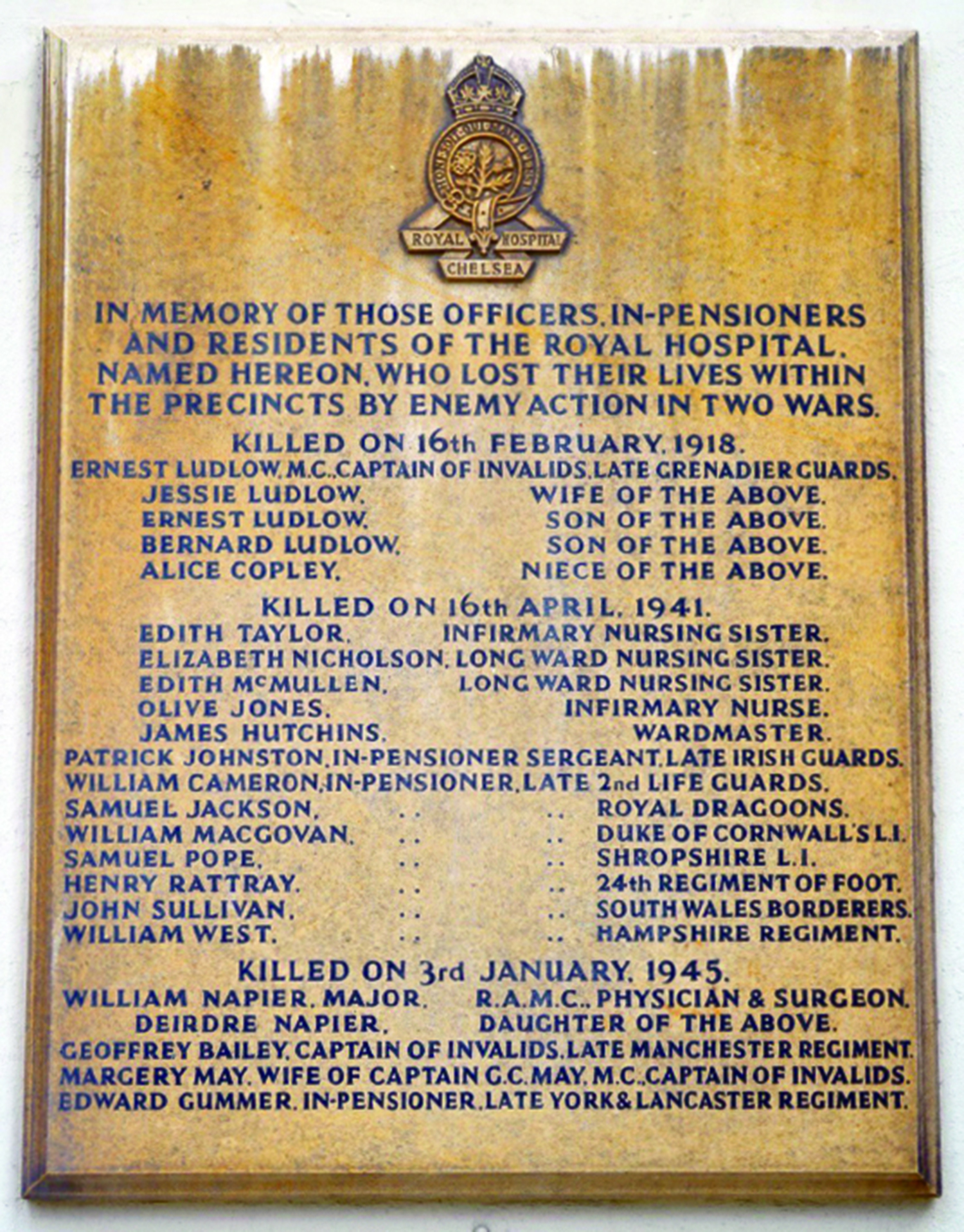

This board displayed on the Colonnade lists those who died on 16 April 1941.

Heroes of the Royal Hospital

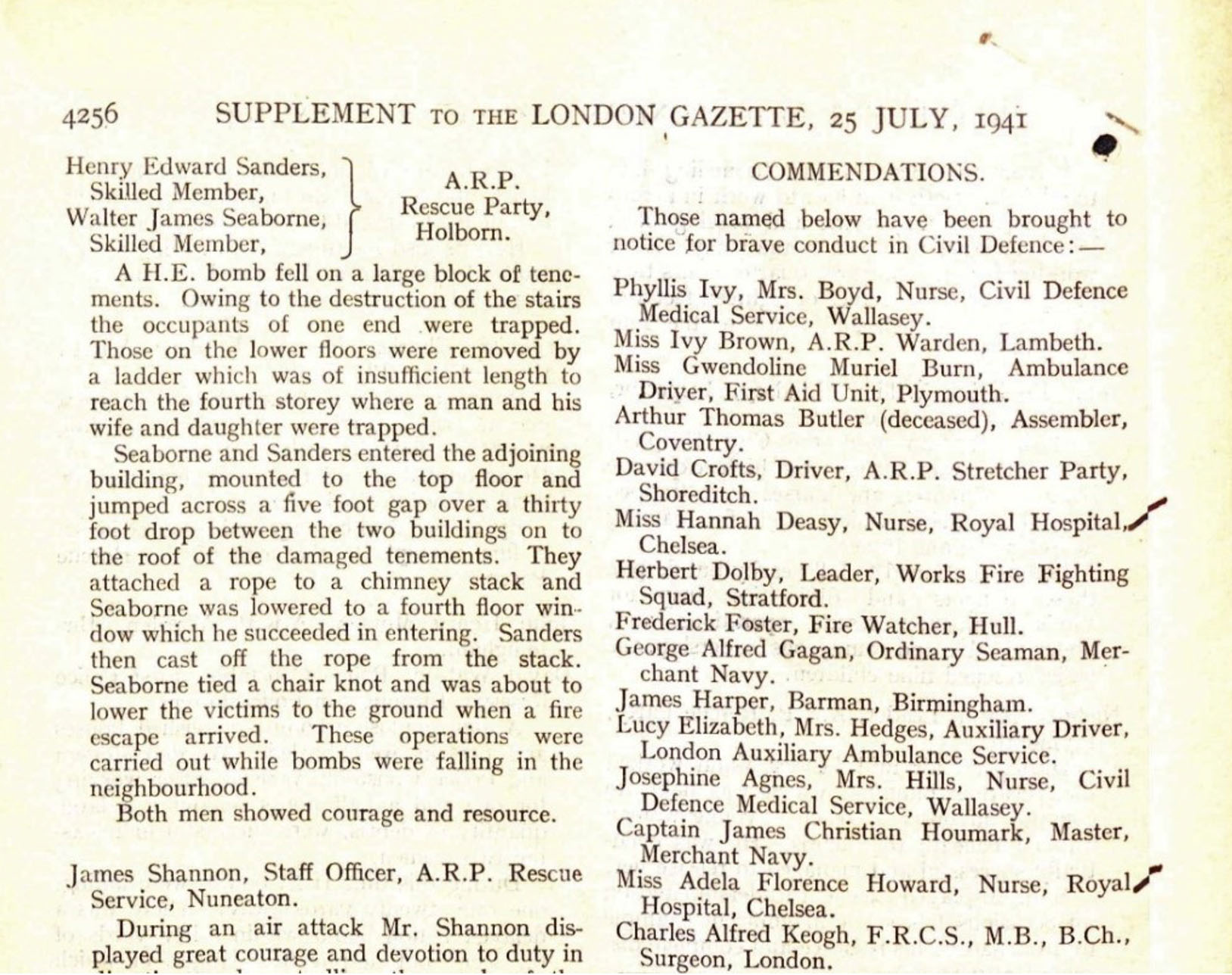

A number of Royal Hospital staff and residents were recommended for Commendations for Gallantry.

Sister Christobel May was “an inspiration”

Sister May was in the Colonnade when the blast struck, fracturing her leg and damaging both her eyes -one permanently. She declined offers of help twice, “directing them to attend first to her In-Pensioner patients” and “displayed great fortitude”.

Mrs Rachael Nash “remained cool and collected”

The surgeon’s wife was undeterred by the damage to the First Aid room and “immediately began clearing up the plaster and debris and the organised treatment of casualties, most of whom she bandaged herself. She continued to work as a volunteer until the last patient was removed.”

Sergeant Frederick Herbert Harrison was “indefatigable”

Sergeant Harrison was “a fine example to all”, helping to bring fires under control before the fire brigade arrived and was “indefatigable in rescue work, removing patients from the damaged buildings at great personal risk”.

Captain William Lockley “set a magnificent example”

Captain Lockley “displayed courage and initiative of a high order”, endangering himself as he searched the wards for the injured as well as “searching the burning bomb crater thick with smoke and fumes”. He also organised stretcher and rescue parties and extinguished incendiary bombs.

Mr James Beezley “displayed great initiative”

Mr Beezley coupled up lengths of hose from a standpipe to bring fires under control before helping with rescue work. His “energy and resource… were of the greatest value”.

Nurse Adela Florence Howard showed “devotion to duty”

Nurse Howard who was in the worst-hit ward was “flung across a bed next to another in which an in-Pensioner was killed outright”. She and another nurse then put out a fire, helped to remove patients and helped in the First Aid room, before putting out another fire showing outstanding “devotion to duty and disregard of self after being so badly shaken”.

Nurse Hannah Deasey’s resourcefulness was “of a high order”

After the windows were blown in on Nurse Deasey’s ward, she checked her own patients were unhurt before moving to help Nurse Howard to put out a fire on her ward. She then climbed through a window to another ward with a blocked entrance and helped rescue patients before helping in the First Aid room and putting out another fire with Nurse Howard demonstrating “resource and devotion to duty…of a high order.” Hannah Deasey was just 27.

Two outstanding nurses

Although the Governor spent several months striving to get the bravery of all the individuals involved, only Nurses Howard and Deasey were officially acclaimed.

Although Soane’s Infirmary is no more, we remember those who lost their lives there 80 years ago and the bravery of the men and women who were prepared to risk their own safety to help others on that memorable night.

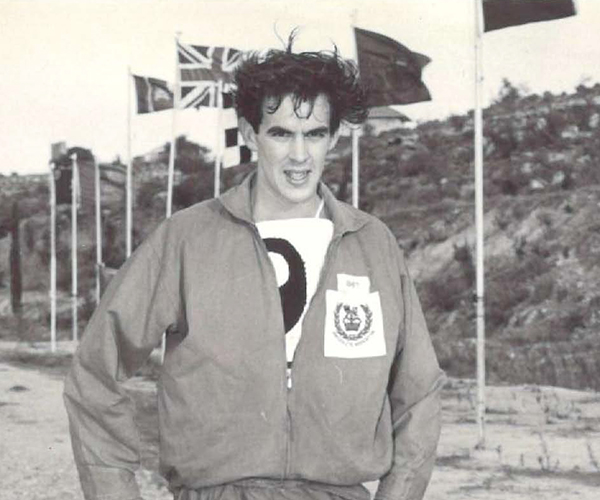

Three wreath-laying ceremonies were held today, the first at the National Army Museum, with a wreath laid by National Army Museum Director, Mr Justin Maciejewski DSO MBE and a brief Act of Remembrance given by Royal Hospital Chaplain, Revd. Steven Brookes.

Two other small ceremonies also took place, with wreaths laid at the current site of the Royal Hospital’s Infirmary by Matron Jayne Cumming RRC and on the Colonnade in the Hospital’s Figure Court, where a plaque commemorates the names of those lost on that tragic day.

Wreath-laying at National Army Museum