WWII Prisoner of War John Humphreys reunites with commando knife used to escape capture

30th January 2024

John Humphreys OBE DL celebrated his 102nd birthday this month. He visited the Royal Engineers Musuem where he was given a tour of the Barracks and Museum, and was renunited with the commando knife he used to escape his second capture during the Second World War.

Very few escape stories rival that of John Humphreys, the WWII Prisoner of War who was detained twice and twice evaded his captors.

Read more about John's story:

From Army childhood to boy soldier

John chose the Navy. It was only when he was checking through his paper that he realised his father had sent him to sit the exam for the Army technical school. His future had been decided for him. He passed the exam and was sworn into the Army as a boy soldier in 1936. A couple of weeks later, John was on a troop ship bound for England.

At his military school near Chepstow, John learned standard subjects in the evening and did Army training during the day. As a Royal Engineer – his father’s choice – John had to have a trade and he learned to be a fitter and turner. “In 1936 you just did what you were told,” he remembers.

After three years, John joined a Royal Engineers training battalion: “I was still technically a boy and paid as a boy – 11 pence a day.” Soon after, war broke out and John was promoted:

“The training battalion was flooded with volunteers and there was a need for instructors. I was an acting unpaid Lance Corporal, teaching men old enough to be my father the basic rudiments of military engineer. Still on 11 pence a day I might add. Then in January 1940, I became an adult. My pay went up to six bob a day. I was in wonderland!

Captured in Tobruk, Africa

John soon started to want something more.

I got fed up with being an instructor because soldiers were going to France and, being young, I was mad keen. I wanted to go as well. But Dunkirk occurred and instead of France I went to Africa. The Italians were trying to capture Egypt and the Suez Canal. When the Italians were defeated the Germans came in.

In 1942 John was in Tobruk. "I was tasked with repairing all the harbour installations for demolition, if the Germans broke in. Which of course they did." He explains what happened next:

I was busy blowing up cranes and water towers around the harbour, and a couple of tanks appeared – I thought they might be ours. I looked closely and could see that they were German. So I just dropped into a nearby trench and stayed in the bottom while the tanks went over the top. The following day I tried to escape. The Germans were all over the place; they’d captured Tobruk. I tried to get out, but I got mixed up in a fire fight and hit in the head. The Germans put me in a vehicle and sent me to Benghazi – to the hospital. When I came out of hospital I was sent to Ancona, in northern Italy, as a prisoner of war.

An ingenious escape

I realised that the only way I could escape was if I could speak fluent Italian. So I acquired a Hugo’s Italian Grammar from the Red Cross. I used to sit outside and memorise Italian until I had a large vocabulary. Then I realised I would have to practise. Where I used to sit outside was quite near a sentry box. So I called out to the sentry in Italian, and he looked at me, and he said ‘Yeah?’ And I started talking to him. He was obviously bored stiff in that box all day, so he was quite pleased to have somebody to talk to! Unbeknowing, I acquired his accent – which was the Italian version of Oxford English!

When John arrived at the camp, he’d been wearing clothes suitable for Africa, so he was issued with a Greek Army uniform by the Italians. Fortunately for John, the uniform was very similar to an Italian soldier’s one.

John found two friends who were also eager to escape. “One roll-call night, I said to Dick and Bernard, ‘I’ll march you along as though you were prisoners.’” Soon after, they put John’s plan into action: “I made them walk in front of me and it looked like I was escorting them, until we go near the sentry that guarded the wicket gate. I told him – in Italian of course – that I was taking these two to the Commandant for punishment.” The plan succeeded and the prisoners found themselves on the other side of the perimeter wall.

“A narrow squeak”

The men started to walk south, stealing grapes, figs and tomatoes from the fields and trees to feed themselves. After about a week, they came across a farmer:

“He looked at us said, ‘It’s obvious you’re British prisoners-of-war. I’ll give you some civilian clothes and you can give me your uniforms’ – the Italian country people hated the Germans. So we did a swap and carried on.”

Some time afterwards, they came to a motorway, where they had a narrow escape, as John explains:

We had to cross an autostrada, or motorway. I was walking about 100 yards ahead of the others, so if I ran into trouble, they could go to ground quickly. I waited by the autostrada and a column of German vehicles started going by. At the end of the convoy were motorcycles and sidecars. The last one stopped right opposite me, and that’s when my heart went into my boots. He had a bloody big machine gun on his side-car. There was nowhere I could go. He called out to me in very broken Italian – where could he get water for his motorbike? So I explained to him that if he carried on for another five or ten minutes he’d come to a river. He looked at me rather strangely, but eventually he said ‘OK’, got back on his bike and cleared off. That was a narrow squeak.

Eventually, the soldiers reached Bari, where the Allies were coming ashore, and realised they were “home and dry”. From there, they travelled to Algiers and boarded a troopship back to England.

“Everyone was getting ready for D-Day”

When John finally got home, he was told he’d been selected for commission – but this would involve weeks of delay and he was reluctant:

It was common knowledge that everybody was getting ready for D-Day. So I asked my company commander if I could go back into the ranks and not be commissioned. He flatly refused. Then in the barracks there was a poster of this chap hanging from a parachute, asking for volunteers for airborne forces. So I filled out an application form and gave it to the company commander – who tore it up and threw it out.

John refused to be deterred. There was an address for the Colonel and Commandant of the Airborne Parachute Forces on the corner of the poster:

So I wrote a letter to him saying, ’You’re wasting your time putting these posters up, because when we volunteer we get turned down’. Thirty-six hours later I was doing my para selection course! I finally qualified and was posted to the 1st Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers, stationed at Donnington, Lincolnshire. The next thing was the operation at Arnhem, we dropped into Arnhem.”

Action at Arnhem

At Arnhem, John and the paras were tasked with capturing the bridge, but things didn’t go according to plan:

We captured the north end of the bridge, but couldn’t capture the south. The RAF had refused to drop us there. What was left of my troop were told to occupy the school that overlooked the north end of the bridge. Whoever occupied the school controlled who came and went on the bridge. So, we went into the school, broke the glass out of the windows, filled the baths with water – the usual stuff you do when you’re fighting in street warfare. If somebody starts chucking grenades and mortar bombs and things like that, the first thing you need to do is to get rid of anything that could possibly injure you.

I was positioned in the corner, overlooking the bridge, and to my right was a park. The Jerrys came over the bridge in half-tracks – a small, armoured vehicle – so we fired down into them. Then another lot came through the park and got the same treatment. I had a Bren gun and Sid, my number two, would fill the magazines. I said, ‘Get these magazines filled’ and he just fell to one side. He was stone dead.

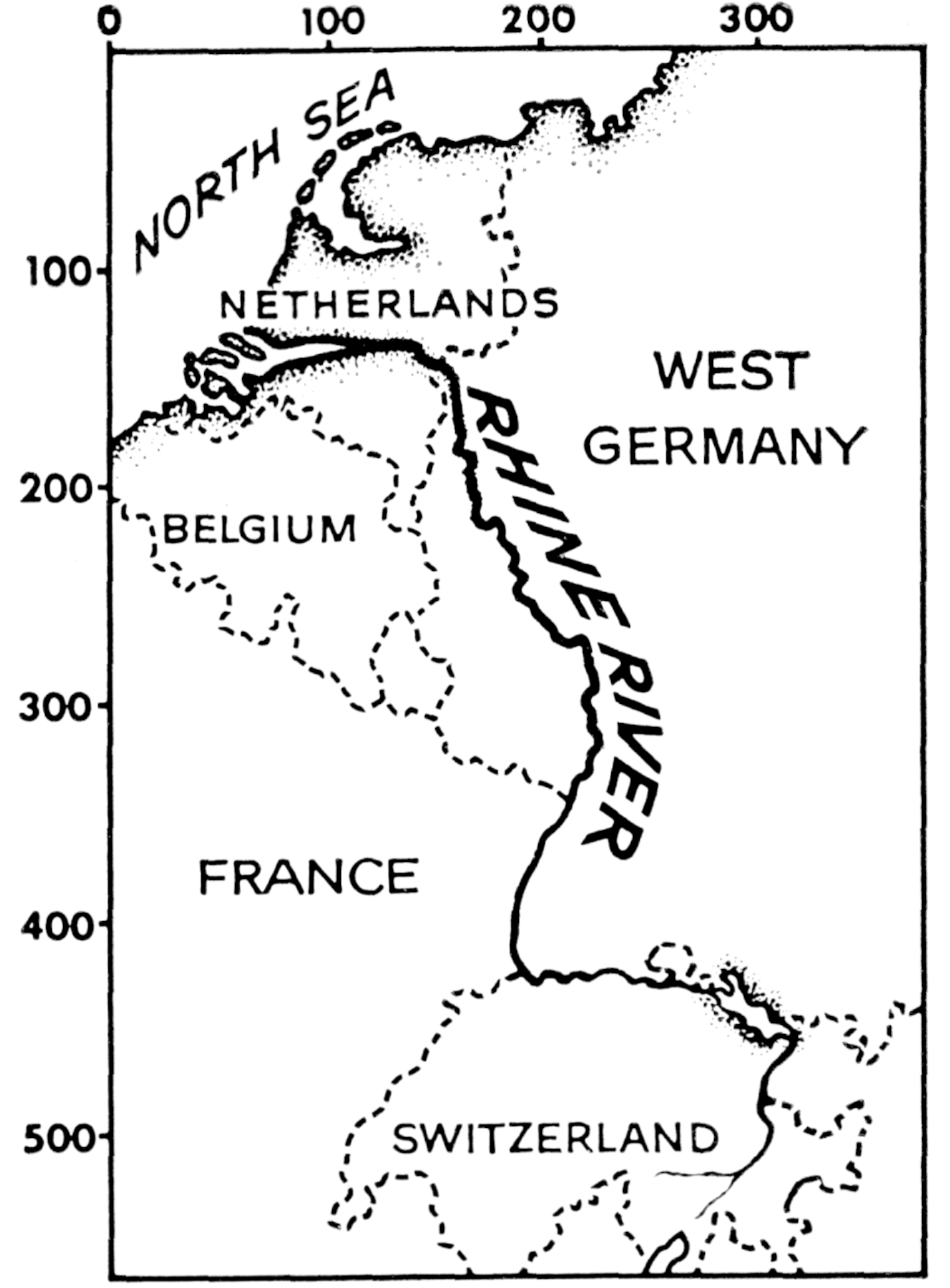

This went on from Sunday evening until when Wednesday afternoon when we ran out of ammunition and were forced to surrender. Well, I didn’t want to surrender, so I tried to escape from the school. There was a row of houses opposite, with gardens facing us. I took three of my stick with me. I said, ‘I’m going to make a run for it’ and they said ‘OK’. We ran across the road, got into the gardens and climbed over the garden walls, heading for the river. I lost one along the way, then John Maddy got stuck on one of the walls and I had to go back for him. Then there was a burst of machine gunfire and I saw the brickwork beside me fill with holes. I pushed John off the wall, dived to the right and ran like hell towards the Rhine.

As he climbed over the last wall, John thought he’d made it but “instead of the Rhine there was a depot of trams. It was also full of Germans.”

“Back in the bag”

John found he had an unexpected weapon when he dropped down into the tram depot:

I landed at the feet of two German soldiers, who took one look at me and ran like hell. I had five days’ growth of dirt, blood, muck – I must have looked a bit grim! The Germans went one way and I went another, behind the trams. I thought their big steel wheels would shield me from any small arms fire and I’d be able to work my way down and finally get to the Rhine. But one of the Germans brought up a self-propelled gun, pointed the barrel down and said, ‘If you don’t come out, I’ll blow you out’. So I was back in the bag.”

Although John was interrogated, he wasn’t harmed. In fact, the German major showed his respect for the enemy:

“He said to me, ‘If the British Army had fought in France as hard as you people fought here, we could never have captured France.’ I thought, ‘Well that’s a nice compliment!’”

Nevertheless, John was put in a truck with other British soldiers and taken to a prisoner of war camp.

Two hours to freedom

After his experience in Italy, John wasn’t prepared to submit to imprisonment without a struggle:

When we got to the camp, everybody in the truck jumped out, and ran towards some other POWs, thinking they might find their friends. I stayed by the entrance and looked to see if there was anywhere I could escape. You’ve got to bear in mind I had already been a prisoner of war once, and I had no intention of being a prisoner of war again. I’d do anything to escape.

In the far distance I saw a small brick building. So I went down to look at it – it turned out to be a sort of cookhouse with two stoves. It had two windows in the wall, with three bars down them. All Royal Engineer soldiers carried a jack-knife – a big thing, with a blade and a marlin spike, for splicing wire rope, I used the marlin spike to pick out all the cement around the base of the bars. We got there about 2 o’clock and by 4 o’clock I’d got the bars free.

I went looking for these friends of mine and three of them came down with me when it was dark. Mackay looked at the barred window and said ‘How the hell do we get out of here with those bars on the window?’ I said, ‘Like this’. Then I put my hand on the bottom of the bars and my feet on the wall, and pulled, bending all three bars out. Then it was head out, shoulders out, drop… and that’s it.

Down the Rhine in a rowboat

The Rhine army barges were coming down the river and one of them stopped about 200 yards from us and the crew got out and went ashore. We went on board and tied up against the barge was a rowboat. So we got in and cast off.

The Rhine flows fairly fast, with the righthand side going to Arnhem and the left to Nijmegen. We’d been going down the river for quite a while and it was very early in the morning we heard this very English voice call out ‘Halt, who goes there?’ That was it . We were there – back among the Brits.

“I’m the only one left now”

After this last escapade, John’s squadron was reformed and he was sent to Norway, where he was serving when the war came to an end. He has a medal and diploma from the Norwegian government, acknowledging his contribution there.

Over subsequent years, John’s squadron would meet annually at Donnington, where they were stationed before Arnhem.

“Every September, we’d have dinner in the evening and a church parade on Sunday. The numbers gradually dwindled. At the last one, there were three of us. Two have died, so I’m the only one left.”