To mark Halloween, we’ve been investigating a murky period in the history of the Royal Hospital’s Old Burial Ground. First consecrated in 1691, over 10,000 Chelsea Pensioners, staff and families were laid to rest here before burials ceased in 1854.

Nowadays, the Old Burial Ground is a place for peaceful reflection and remembrance, but it has played a part in a darker period of London’s past.

A craze for cadavers

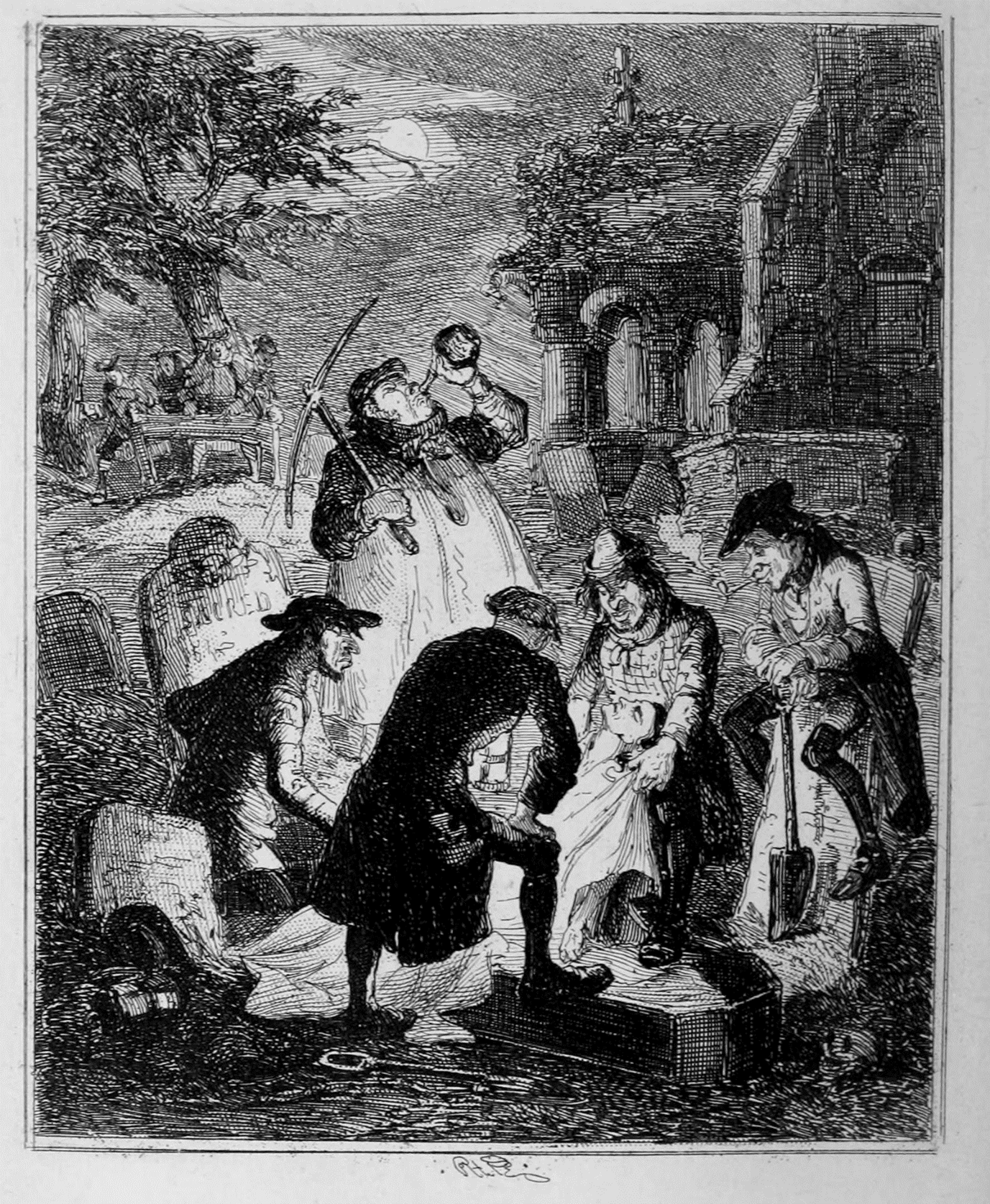

The infamous Burke and Hare murders in Edinburgh in 1828 raised public awareness of Resurrectionists and a group of body snatchers known as the London Burkers soon became notorious for murdering and stealing corpses to sell to anatomists in the capital’s hospitals.

After the London Burkers were tried and hanged at Newgate Prison the Anatomy Act of 1832 was passed, providing a legal supply of corpses for medical education and research.

Grave robbers at the Royal Hospital

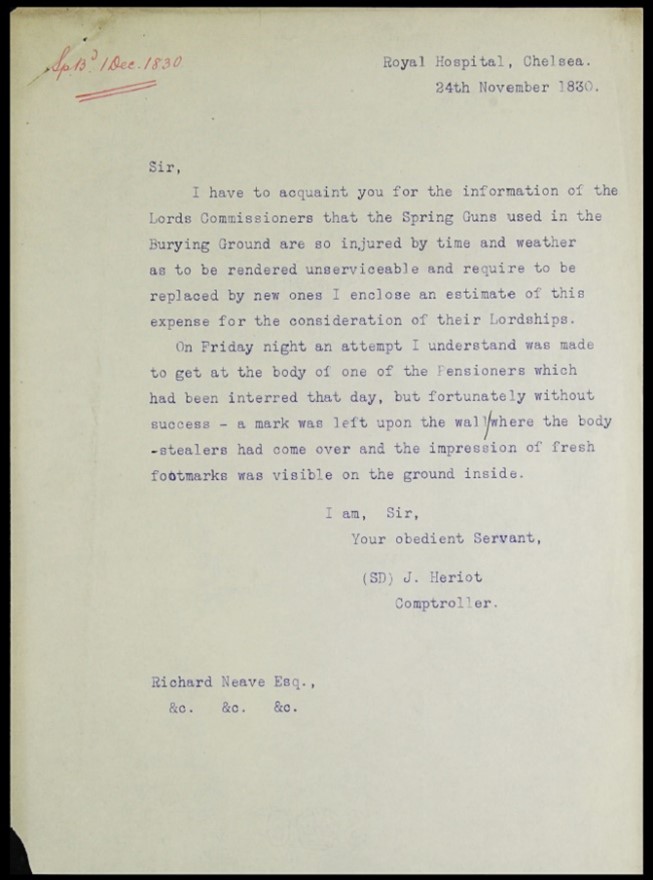

On Friday night an attempt I understand was made to get at the body of one of the Pensioners which had been interred that day, but fortunately without success – a mark was left upon the wall where the body-stealers had come over and the impression of fresh footmarks was visible on the ground inside.

This was not the first time that grisly thefts from the Old Burial Ground had been reported. In 1756, records show that “several of the Dead Bodys of the Pensioners have lately been taken away out of the Burying Ground”. Despite efforts to deter grave robbers by fixing the surrounding wall, the following advertisement issued 32 years later shows that these were unsuccessful:

Whereas two DEAD BODIES have been stolen from the Burying Ground of this HOSPITAL, and for the better discovering of the offenders FIVE GUINEAS will be given by the Treasurer to any person who shall give Information of the Parties concerned in the robbery.

Cemetery Guns

Cemetery guns – also known as spring guns – became a common way to deter Resurrectionists. These weapons were triggered by stepping on a wire running across the ground but, as surgeon Bransby Blake Cooper explained, they were easily outsmarted:

If a Resurrectionist proposed to work where these instruments of danger were used, and when he was not intimate with the grave-digger or watchman, he sent women in the course of the day into the ground, generally at a time when there was a funeral, to note the position of the pegs to which the wires were to be attached. Having obtained this information, the first object of the party at night would be to feel for one of these and having found it, they carefully followed the wire, till they came up to the gun, which was then raised from the surface of the grave mound, (its usual position,) and deposited safely at its foot. I have been told that as many as seven bodies have been taken out of one grave in the course of a night, under these circumstances. The grave being filled up and restored to order, the gun was replaced precisely in the spot it had previously occupied.

The Royal Hospital installed spring guns in the burial ground in 1819, but by 1839 they had become “so injured by time and weather as to be rendered unserviceable and require to be replaced by new ones”. However, Neave’s request to install new guns was denied by the Royal Hospital’s Commissioners who ‘having taken the opinion of the Solicitor of the Hospital as to the legality of using Spring Guns in the Burying Ground, directed me to desire that you will cause those now placed there to be removed therefrom, it being their Lordships intention to adopt some other mode of protecting the said ground”.